7. Is Posen-Wartheland Prussian?

Coat of Arms of the Prussian Province of Posen

Coat of Arms of the Prussian Province of Posen

The redrawing of international boundaries is a tricky thing at best and a nightmare at worst. At the end of the First World War following the defeat of Imperial Germany, the Prussian Province of Posen - minus the small Fraustadt enclave annexed to Silesia and the western part including Meseritz, Schwerin and Schneidemühl - was, along with most of West Prussia, detached from Germany and ceeded to Poland without a plebiscite. The result was that Poland acquired - along with those living in that part of Upper Silesia (Oberschlesien) that was detatched from Prussian Silesia - a large German minority that was to later give Hitler one of many pretexts for war against Poland in 1939. It need not have been so. Had the Allied Commission responsible for the detatchment of Polish speaking areas of Prussia been fair and honest in Silesia, Posen and West Prussia as it had been in East Prussia, a clean international border between the German- and Polish-speaking parts of Prussia could have been established. But it wasn't. The East Prussian plebiscite results had shocked the Poles who had counted on the largely Slavic Masurian people to vote for Poland - they didn't and regarded themselves as culturally Prussian and German. The overwhelming majority in favour of Germany forced the Allies to allow Germany to retain all the plebiscite area, minus Soldau, which was given to Poland because of its strategic railway line - never mind what the German inhabitants thought.

The plebiscite in Upper Silesia (Oberschlesien) also went in favour of Germany, with 60% of the population voting for Germany, and 40% for Poland in spite of Polish terrorist activity under the leadership of Korfanty. The Italian Commission recommended that the area be immediately returned to Germany but the French, determined to 'punish' Germany as much as it could, insisted on a partition, giving the the best idustrial part to Poland together with a very large German population in the cities, including the capital, Kattowitz.

Some years ago I made a study of West Prussia (the 'Polish Corridor') and, based on the voting patterns in East Prussia, concluded that between 60 and 70% would have voted for retention within Germany. However, President Wilson of America had very foolishly (and in violation of his own principle of the 'self determination of peoples') promised Poland access to the sea which meant cutting right through Prussian territory. Because of his undertaking, no plebiscite was therefore taken in West Prussia which, apart from Danzig which was made a 'Free State' (under Polish customs control), meant the vast part of the Province, together with its German population, was given to Poland. A small part of the German-retained portion of Posen was joined to a remnant of West Prussia likewise retained and from it was created the Grenzmark Posen-Westpreussen. Because of the impracticability of administering such a widely separated patchwork of kreise these were eventually partitioned between Brandenburg and Pomerania.

But unlike West Prussia, East Prussia and Silesia, which had for centuries been unquestionably Prussian (or, in the case of Silesia, Austrian), the Posen area was not historically German. Indeed, it was known as Great Poland. Prussia first obtained this area in the Second Partition of Poland, lost it briefly to the Grand Dutchy of Warsaw (a puppet state set up by Napoléon), and then regained some of it in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna. Apart from in the border regions, though, the population was overwhelmingly Polish.

Flag of the Prussian Province of Posen

Flag of the Prussian Province of Posen

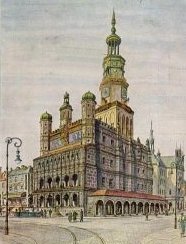

Beginning as a small stronghold in the 9th century, Poznań (Posen) was at one time the capital of Poland and the residence of Poland's first two sovereigns. The Polish cathedral was erected there in 968. In the 13th century a new section, now known as Old Town, developped on the left bank of the Warthe (Warta). The town received municipal rights in 1253. With dury-free trade privileges, Poznań became a major European trade centre, it's economic and cultural growth reaching a peak in the 15th and 16th centuries. It declined during the 17th century through fire and wars.

In 1793 Poznań was annexed to Prussia and renamed Posen. Germanization of this city had, however, begun as early as the 13th century with the arrival of the first German immigrants. So there was a substantial population even before Prussia acquired the territory (which was known as South Prussia or Südpreussen). Anti-Polish and anti-Catholic measures were enacted by Otto von Bismarck in the 1870s. In 1886 a commission of colonisation was organised to buy Polish land for German colonists, but the Poles established cooperative credit organisations and continued to defeat Prussian efforts to control Posen. At the beginning of the 20th century much building was done to give the city a Prussian complexion.

In 1793 Poznań was annexed to Prussia and renamed Posen. Germanization of this city had, however, begun as early as the 13th century with the arrival of the first German immigrants. So there was a substantial population even before Prussia acquired the territory (which was known as South Prussia or Südpreussen). Anti-Polish and anti-Catholic measures were enacted by Otto von Bismarck in the 1870s. In 1886 a commission of colonisation was organised to buy Polish land for German colonists, but the Poles established cooperative credit organisations and continued to defeat Prussian efforts to control Posen. At the beginning of the 20th century much building was done to give the city a Prussian complexion.

At the end of the First World War the Polish population rose up against their Prussian overlords, seizing about 70% of the territory by force of arms even before the settlement of the Treaty of Versailles, the border roughly representing the ethnic division between Poles and Germans. As such, then, it would have made a fair Polish-German frontier. My own detailed study of the ethnic divisions in the Province led me to draw up a partition proposal in 2004 which is close to the de facto line established by the rebels as shown in the map below (click the map to see it in full-scale):

I am quite sure that had there been a proper plebiscite in the Province, and had the boundary commission been honest and fair, then the red line I have drawn would have been the approximate partition boundary. This should have been the territory yielded by Prussia to Poland at the end of 1918. In fact, considerably more was.

Poznań (Posen) prospered between the two wars, most of its German population emigrating to Germany following its loss by Prussia. The city was devastated in the Nazi invasion of 1939 and its inhabitants deported or exterminated by the fascist terror-machine. The city, together with the whole Posen territory, plus territory further east as far as Lódz (Litzmannstadt) was annexed to the Reich and the Province renamed the Wartheland after its principle river. The Soviet Army laid seige to the city in 1945 leaving it in ruins. It was rebuilt after the war and has become the administrative, industrial and cultural centre of Western Poland. The population of the city today is about half a million inhabitants.

In June 1956 the industrial workers of Poznań rose up in rebellion against their Communist overlords causing a crisis in the Polish Communist leadership as well as the Soviet block and resulted in the establishment of a new Polish régime headed by Władysław Gomulka. 53 people were killed and over 200 were wounded. Perhaps they were inspired by the uprising against Prussia at the end of the First World War. At any rate, there does seem to be a 'revolutionary spirit' amongst the Poznań Poles.

There is no question in my mind that neither Prussia nor Germany had or has a legitimate claim to the whole of the old Imperial Province of Posen, in spite of all the development of the territory accomplished under Prussian rule. The border areas are, however, another matter, as was at least acknowledged by the Allied Boundary Commission which gave some of the German-speaking parts to Germany between 1919 and 1923 - they should have been given far more.

Created 06.12.2004 | Updated 13.05.2012

Copyright © 2004-2012 SBSK Preussens Gloria

Alle Recht vorbehalten - All Rights Reserved